I recently shared how a team I worked on designed an API using code. The goal was to show that code can be used as a tool for design, and how prototyping can give us fast feedback on the quality of our design.

In this writeup we’ll look at how we might use code to design API behavior. We’ll use Python and FastAPI like we did in the last writeup, so you may want to read it first before moving forward.

Our example: Bookmark API

We’ll continue to use the Bookmark API example. We’ll add a reading list feature that allows us to queue up bookmarks to read later and mark them as read once we’ve visited the link. We should be able to archive queued items, read items, and reread items.

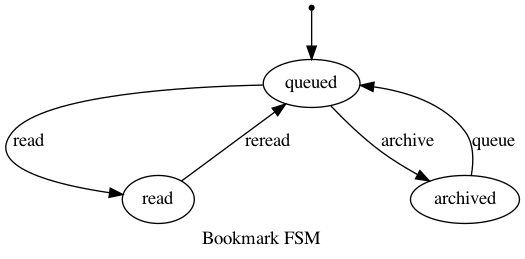

We’ll use a finite state machine (FSM) to model the interaction. The FSM allows us to define the states a bookmark can be in—such as queued or read—and the available actions a person can take in each state—such as reread or archive.

We looked at several patterns in the last writeup such as the Representor Pattern or Repository Pattern. The FSM is another helpful pattern. With it we can define all valid paths through our software and prevent users from taking invalid paths. We can graph those paths and get a feel for the interaction, to make sure it makes sense, and to prevent bugs from creeping in.

For our reading list feature, the states and actions may be expressed with enums in Python.

class BookmarkState(Enum):

QUEUED = "queued"

READ = "read"

ARCHIVED = "archived"

class BookmarkAction(Enum):

READ = "read"

ARCHIVE = "archive"

REREAD = "reread"

QUEUE = "queue"

While this code captures the possible states and actions for our feature, it doesn’t show us the possible transitions between states. For that we’ll need a way to define how they interconnect.

Designing the state machine

There are several good Python libraries for FSMs. However, for this example we’ll implement our own.

We’ll define two classes to use for our FSM: one to define a possible transition between states and another to keep states and transitions along with the initial state for the FSM.

@dataclass

class BookmarkTransition:

action: BookmarkAction

from_state: BookmarkState

to_state: BookmarkState

@dataclass

class BookmarkFSM:

initial: BookmarkState

states: List[BookmarkState]

transitions: List[BookmarkTransition]

With these classes we can model our reading list functionality.

bookmark_fsm = BookmarkFSM(

initial=BookmarkState.QUEUED,

states=list(BookmarkState),

transitions=[

BookmarkTransition(

action=BookmarkAction.READ,

from_state=BookmarkState.QUEUED,

to_state=BookmarkState.READ,

),

BookmarkTransition(

action=BookmarkAction.ARCHIVE,

from_state=BookmarkState.QUEUED,

to_state=BookmarkState.ARCHIVED,

),

BookmarkTransition(

action=BookmarkAction.QUEUE,

from_state=BookmarkState.ARCHIVED,

to_state=BookmarkState.QUEUED,

),

BookmarkTransition(

action=BookmarkAction.REREAD,

from_state=BookmarkState.READ,

to_state=BookmarkState.QUEUED,

),

],

)

The code above defines four possible transitions.

- Visit - change read status from

queuedtoread - Archive - change read status from

queuedtoarchived - Read - change read status from

archivedtoqueued - Reread - change read status from

archivedtoreread

Now that we have code to define the FSM, we need code that enable us to trigger actions and prevent us from taking invalid actions. For instance, we can’t reread something we haven’t read yet.

We’ll write two functions and an exception to make this possible.

class TransitionError(Exception):

def __init__(self, message):

self.message = message

def transitions(state: Enum, fsm: FSM) -> List[Transition]:

return [t for t in fsm.transitions if t.from_state == state]

def trigger(action: Enum, current_state: Enum, fsm: FSM) -> Enum:

ts = transitions(current_state, fsm)

next_action = next((t for t in ts if t.action == action), None)

if not next_action:

raise TransitionError(

f"Can't trigger {action.value} for state {current_state.value}"

)

return next_action.to_state

The transitions function will give us all of the available transitions for a given state—it will tell us we can only reread something we’ve read. The trigger function will try to invoke an action given the current state. If we try to trigger an invalid transition, it throws our TransitionException exception.

More on boundaries

We looked at the importance of boundaries in my last writeup. Here we can see how we use Python’s exceptions as a way to communicate failure from our core code. Our intention here is to raise a TransitionError and let outer layers handle it, in our case it’s the API layer.

We’ll see below how the API layer will catch this error and convert it to an HTTP error response. This allows us to write our core code that has no concept with HTTP while handling it in an HTTP-aware layer.

Graphing our state machine

It would be helpful to see what our FSM looks like. We could write it out by hand with teammates on a whiteboard. Most of the Python FSM libraries have graphing functionality, but it’s not too hard to add support for graphing to our custom code.

from graphviz import Digraph

def graph_fsm(fsm, name, label):

g = Digraph(

name=name,

node_attr={"shape": "oval"},

graph_attr={"nodesep": "1.5", "label": label},

)

g.node("start", shape="point")

g.edge("start", bookmark_fsm.initial.value)

for t in fsm.transitions:

g.edge(t.from_state.value, t.to_state.value, label=t.action.value)

g.render(name, format="png")

graph_fsm(bookmark_fsm, "bookmark-fsm", "Bookmark FSM")

This code converts our FSM into a graph using Graphviz. The render function will create and save a bookmark-fsm.png file that maps our states and transitions.

Seeing the FSM helps us look for the gaps and make sure we understand the interaction.

Hooking it into our API

Now that we have our core interactions finished, we’re ready to hook it into our API layer. We’ll create a POST request to a URL with the state in the URL. You might prefer changing the state directly on the Bookmark, and that works, too.

@app.exception_handler(TransitionError)

async def fsm_exception_handler(

request: Request,

exc: TransitionError

):

return JSONResponse(

status_code=400,

content={"detail": exc.message}

)

@app.post(

"/bookmarks/{bookmark_id}/{action}",

response_model=BookmarkItem,

tags=["Bookmark"],

)

def update_bookmark_status(

bookmark_id: uuid.UUID,

action: BookmarkAction

):

bookmark_record = storage.find_by_id(Bookmark, bookmark_id)

next_state = trigger(

action,

bookmark_record.data.read_status,

bookmark_fsm

)

new_bookmark_record = storage.update(

Bookmark,

bookmark_id,

read_status=next_state

)

return bookmark_item_from_record(app, new_bookmark_record)

This is where we define a way to handle our TransitionError exception. If that kind of error makes it to this layer, we’ll convert it into a 400 response with some error details.

The update_bookmark_status finds the bookmark based on the ID in the path, triggers a state change, then updates the bookmark record in our storage.

This doesn’t cover all of the situations. What happens if the ID from the URL isn’t in storage? We might want to return a 404 at that point. We’d follow this same pattern of throwing an exception from our core and converting it into an HTTP response.

Sharing possible transitions with clients

We can take this a step further by representing the possible transitions in our API responses. This enables us to write API clients that rely on the responses from the server rather than including the logic and functionality of the FSM.

If our API doesn’t tell the client what it can do, the client would have to figure out what actions are possible on its own. Or the developer would have to duplicate the FSM logic on the client. This creates a stronger coupling between the client and server.

For our API we’ll add in links to the responses to express the available transitions. We’ll modify our representors to include these links. We’ll use a pattern called RESTful JSON that’s minimal and easy to use. After implementing it, an initial “queued” response may look like this.

{

"url": "/bookmarks/f7bddb25-3ee0-46a6-a07e-2417996892f4",

"data": {

"bookmark_url": "https://smizell.com",

"accessed": "2020-12-20T04:38:28.710000+00:00",

"title": "Stephen Mizell's Personal Site",

"description": "Personal website of Stephen Mizell",

"read_status": "queued"

},

"read_url": "/bookmarks/f7bddb25-3ee0-46a6-a07e-2417996892f4/read",

"archive_url": "/bookmarks/f7bddb25-3ee0-46a6-a07e-2417996892f4/archive"

}

There is no reread_url here because the bookmark read_status is queued—reread isn’t a valid action. If we call the read endpoint with a POST method in our API, it will update our bookmark to look like this:

{

"url": "/bookmarks/ae884a33-6101-4025-a197-d4985ad6a4dd",

"data": {

"bookmark_url": "https://smizell.com",

"accessed": "2020-12-20T04:38:28.710000+00:00",

"title": "Stephen Mizell's Personal Site",

"description": "Personal website of Stephen Mizell",

"read_status": "read"

},

"reread_url": "/bookmarks/ae884a33-6101-4025-a197-d4985ad6a4dd/reread"

}

Now we see one transition for the read state. If we trigger this it will put it back into the queue.

This design weakens coupling by reducing the logic the client needs to know. The client doesn’t need have every state and transitions programmed into it, but rather it just needs to know what transitions to be on the lookout for. Client code will break less often.

How this helps

Designing behavior this way has several benefits.

- It changes how we test. There’s no need to test the core logic through the API layer since it’s isolated. We don’t need to set up a network and database to make sure the bookmark FSM works correctly. We can directly test the FSM, and the API layer can rely on the core code to work.

- We can do our design thinking separate from the API layer. We don’t have to use an API client to make API calls as we prototype a feature. We kept HTTP and JSON details out of the discussion to let us design apart from them.

- We can generate graphs that we can include in our documentation. This helps communicate the design to others during development and after deployment, especially for those who haven’t worked in code before.

- We can surface the current state and available actions in an API or UI which gives hints to users on what they can do in that state. This is better than requiring clients to include the FSM or figure it out through trial and error.

An FSM enables us to think through and validate a design, prevent some categories of bugs, communicate the interaction to others, and weaken the coupling between a client and a server. It lets us go beyond designing resources in an API by helping us work through how the resources help the user or client work toward a specific goal.